Come Ruin or Rapture

Paris 2023 Galerie Marguo solo multimedia exhibition

Has harmony ever existed within our world?

With equal parts tenderness and violence, Come Ruin or Rapture confronts the resilience of nature, inviting us to contemplate the dubious philosophy of human existence and its callousness towards environmental subjugation and each other. In dismembering the intrinsic value of seemingly contradictory entities, Rogers makes a case for the forces of nature as inherent to life itself, whether it blossoms from beneath our feet or not.

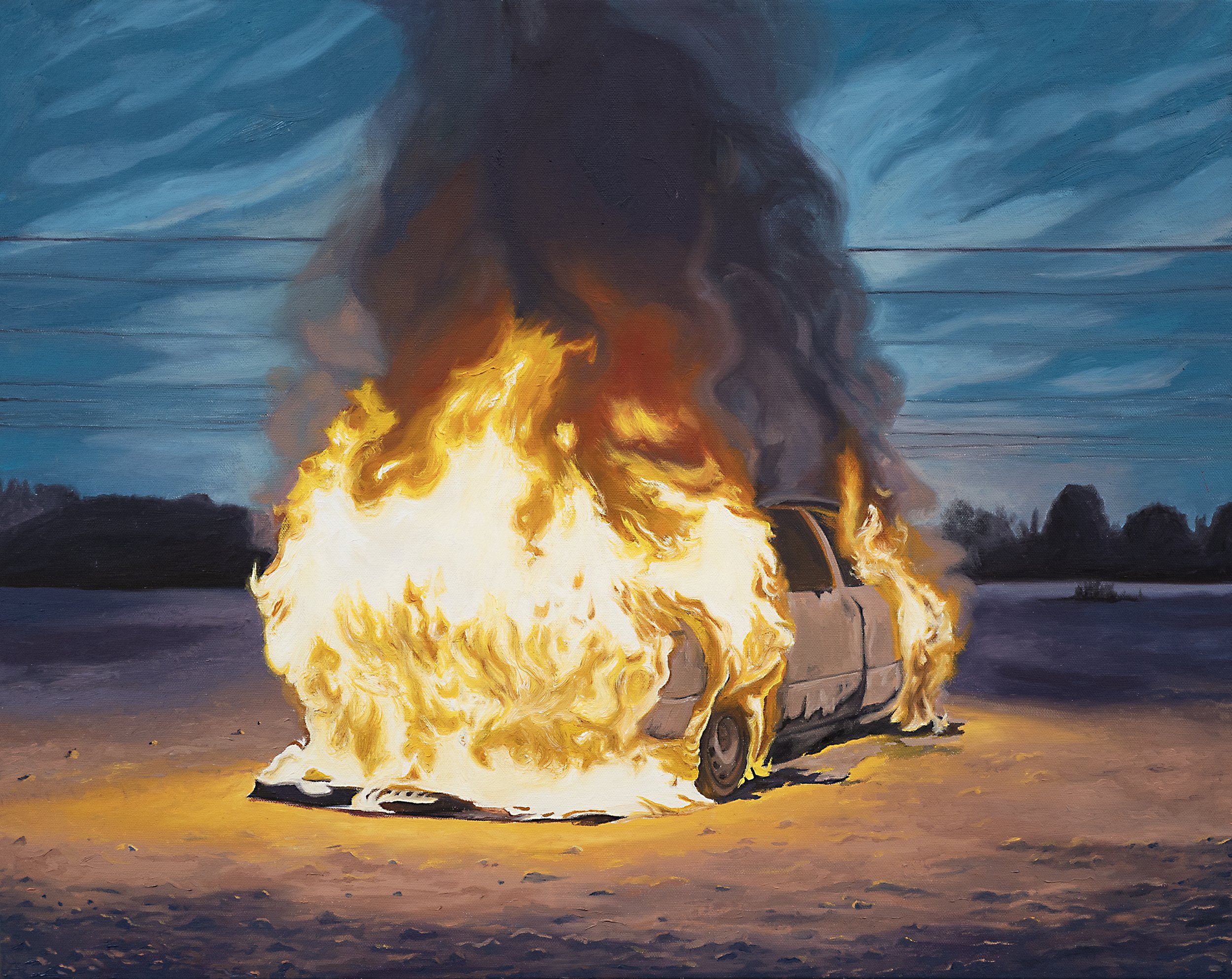

In the series of oil paintings comprising Come Ruin or Rapture the artist centers the immortal rigor of grass; the primal lush carpet that caresses the earth and softens the shells of manufactured existence as they wreak havoc on her landscape. Rogers recalls childhood memories of visits to see her grandmother who lived by a wild meadow where she would fall into its dewy arms, embracing cool sensations of freedom. Around her, the burned-out shells of cars and an occasional roaming horse would cushion the atmosphere. Her figures do the same, threading their fingers through its tendrils with an implicit eroticism. Grass is the living canvas in which this series unfolds, giving rise to elements that are ancient, authentic, and organic, as well as those that are new, artificial, and human-made.

This new body of work hones Rogers’ powers of observation, seeking to locate the somatic and metaphysical sites of becoming, where the body – the flesh and muscle of humanity – acts as intermediary between industrial progress and the sensuality of the unbuilt world. Assembling two-channel video, sculpture, portraiture, and digital media we arrive at an inexplicable harmonium where the flaming carcass of a pick-up truck is drawn into perspective by the complex “thrill and sorrow” with which we consume its image.

The two-channel video titled Contemporary Eve plays out as the aural/visual backdrop to this series of works. The title references the biblical role of Eve as the first giver of life, and the first mother of a murderer, the latter of which in this context can be read as the birth of a people resolved to ruin the earth which birthed them. On the right-hand screen, strangers capitulate to the impulses and rhythms of uninhibition. They present the viewer with hands full of soil, oyster shells, ripened fruit pierced with old casket nails, dead bees and bloody pearls demonstrating the directness of our interaction with the raw materials of earth. But there’s something unsettling about this. The ability to hold whole forms, whole ecosystems within our grasp seems to advance Rogers’ conviction that the currency of humankind is power.

This pursuit of dominance is further rendered as individuals dance freely juxtaposed with destruction; imagery depicting humanity’s guilt or lack thereof convey the reality of an Anthropocene atomized from its misdeeds.

In the junkyards of the mind, disturbance begets excitement, destruction begets provocativeness. Running parallel are vignettes salvaged from the dreamscapes of the artist’s mind: car crash simulations, bucking horses and butchery that spin around the duality of existence. Of particular significance is the white horse that opens the film. Standing in as a symbol of sacred strength and endurance, the women’s sexuality is presented as roles removed from victimisation and of their own will.

Come Ruin or Rapture notably interacts with Rogers’ Car Meat Sculpture. An eight-foot rack of accident-impacted car hoods hang dented, primed and painted from meat hooks intentionally resembling the cuts of steak being gutted and sliced in Contemporary Eve. The uncanny brutality of this sculpture speaks to the rich dynamic of capitalist indulgence, desire and death with the automobile and cattle industry existing as two of the largest causes of environmental crisis in our modern age. Viewers are also prompted to consider the structural integrity of the mechanical form under the guise of flesh, alluding to our common destiny. Wielding primitive materials against the synthetic framework Rogers returns to the field of her childhood, crawling into the mechanical husks that are sacrificed to nature.

Millen Louisa

Never Risk a Shell for a Pearl

As a child Fawn Rogers lived in the woods in Medford, Oregon with her mother in a bohemian commune that drew water from the Rogue River and sourced food from the land and government subsidies. Her mother was a born-again Christian who used to tell Rogers that the rapture was coming and she would be left behind with the sinners. “A bar of gold won’t buy a loaf of bread,” she warned Rogers, who would be brought to tears thinking she had been left behind, “It happened”, she would yell to the empty forest if she ever arrived home alone. “It really scared the shit out of me” recalls Rogers. “Eventually I realized it couldn’t happen because I didn’t believe in her god.”

Despite these doomsday declarations, Rogers also remembers the bucolic folly of her childhood, playing in a sprawling field of tall grass beside her grandmother’s house off the Oregon coast. She would close her eyes and run with reckless abandon through the tall blades, squishing her feet in the clover, falling into this living canvas again and again.

Grass is resilient, it will grow anywhere, breaking through any patch of concrete or expanse of asphalt, enveloping everything in its path. This breathing blanket is a sense memory device on par with the Proustian madeleine, and one that the Los Angeles-based artist is thirsty for in this moment when wildfires and drought are ravaging every green space on the planet.

“I'd stay there late into the night with a sense of freedom in the dark, in the dew, and that primal, lush carpet surrounded by burnt, crushed cars and horses,” says Rogers, noting these wild grasses also blanketed a neighboring junkyard filled with abandoned automobiles that were sold for scrap, many punctured by mature ash and maples growing through their windows or trunks. Wild horses roamed the coastline, and children were free to run with them. The touch, the sight, the smell of these romantic idylls recalls a proximity to a bygone wilderness, and wildness that is quickly going extinct as pleasure junkies and corporate raiders, your friends and neighbors, are hastening the demise of Mother Earth.

This collision of childhood references, and real-world destruction, forms the crux of Rogers’ multimedia artistic practice, which operates on the razor’s edge between the sublime and the abyss. In her most intimate show to date, Come Ruin or Rapture, the second iteration of a two-part presentation with Galerie Marguo (which opened this summer as the solo exhibition Burn, Gleam, Shine at K11 Musea in Hong Kong). Rogers is returning to these childhood memories and exploring how they continue to influence her practice two decades on.

As with all of Rogers’ work, this exhibition begins with a two-channel video, Contemporary Eve, which serves as the artist’s notes or sketchpad for the show. Footage of nature prevailing over junkyards oscillates with clips of cars crashing into one another, being crushed by hydraulic compactors, and engulfed in flames in open fields without a first responder in sight to stop this carnage. One Contemporary Eve says fuck everyone and everything and jumps from the driver seat of a car headed into oncoming traffic. Other cars fly off cliffs for sport and decay underwater, as horses swim by. In moments of sensual play, people caress dead bees, bloody pearls, a shell containing construction nails. They rub and pet a square piece of sod. It isFaces of Death meets The Bonfire of the Vanities.

Another touchstone from Rogers’ childhood was racing up mountains of oysters outside shelling facilities off Coos Bay, one of the poorest townships per capita in the United States. The oyster, a symbol of opulence, sensuality, and eroticism, stood in stark contrast to the abject poverty of the local landscape. Her painting series, The World is Your Oyster, explores this dichotomy between the sacred and profane, and digs into the reality of pearls being the result of irritants introduced by humans into the oyster's flesh.

In the two-channel video, Rogers shows images of oysters being grilled at summer barbecues while their shells are dumped by the truckload into piles to be converted into fertilizer. This decadent display is contrasted with the sensual motions of dancers embracing in front of a green screen as bodies roll around in grassy fields and glide like water moccasins through mossy lakes at night. But the pleasure cruise doesn’t last long in Rogers’ practice: ultimately, a horse is struck by a car, and in subsequent clips the remains are processed into chevaline.

Fraught with ecstasy, agony, ruin, and rapture, meat is a ripe terrain for Rogers. She extends—and egresses—the metaphors of consumption in her epic Car Meat sculpture. Made by sourcing the hoods of cars that have been in accidents, Rogers butchers them into choice cuts, then meticulously sands and lacquers them with fine pearl metallic auto paint. These fetish finish objects are then placed onto actual meat hooks on handmade trolleys, which hang and roll along a steel rack that extends eight feet into the air. Car Meat grinds the works of John Chamberlain, Alexander Calder and Ellsworth Kelly—a towering trio of American Modernism—into a timeless conversation about human industry, violence and invention. The palette is drawn from the coat of the Akhal-Teke, known as “the pearl horse” for its distinctive metallic sheen.

Like her crumpled wall relief, Contemplating the Minds of 1000 Strangers, the Car Meat sculpture is a meditation on the foreverness of these objects, which are at once beautiful and destructive, and our relentless addiction to them may well kill our planet. Like the oysters, which are now harboring one of the most deadly bacteria on the planet, their carcasses will be with us for generations to come.

Fertility and rebirth also abound in Rogers’ paintings, which are drawn from the two-channel video, many of which depict extreme vantages of oyster shells, grass, meat, and the shells of burnt-out automobiles. Where Rogers’ previous oyster paintings were full of sparkling pearls and tumescent meat, a painting of a glistening oyster shell against a midnight blue backdrop is defined by the lonely shred of pith hanging off it like a ripped skirt. In a landscape inspired by Andrew Wyeth’s 1948 masterpiece, Christina’s World, Wyeth’s subject crawls around a grassy field in coastal Maine. What you might consider the eastern facsimile of Rogers’ seaside climes in Oregon, as she surveys an expanse of bountiful farm terrain. In Rogers’ painting, her Christina is recumbent in a field with a bombed-outold Ferrari, taking the place of Wyeth’s barn in the background, punctuated by a tree sprouting from the engine block.

“I can’t help but to dismantle intrinsic value in my work. I think about harmonious things that are concentrated and sensual like the sea, the soil, the grass,” says Rogers. “I've always been drawn to the forbidden, the prohibited things that society tells us we shouldn't explore. But in exploring them, I find a sense of freedom, a sense of empathy. I want to be present in a world that is being destroyed.”

Michael Slenske